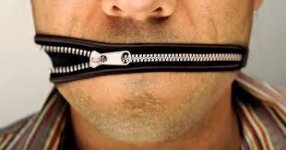

In a world where freedom of expression is the heartbeat of democracy, the idea of censorship sounds like a betrayal. But is it always unjustified? Or can there be moments when democracy must defend itself—even if that means limiting speech?

Censorship is often painted as a tool of dictators, used to silence dissent and suppress truth. Yet, even the most open democracies occasionally reach for this tool. Why? Because freedom isn't absolute—it exists within a framework of responsibility. The freedom to speak should not become the freedom to harm.

Take, for example, hate speech. When rhetoric incites violence or dehumanizes entire communities, can a democratic society truly afford to look away? If unchecked, such speech can fracture nations, fuel terrorism, or even lead to genocide. Here, censorship isn't oppression—it's prevention.

Or consider misinformation. In a digital age, lies can spread faster than facts, influencing elections, public health, and national security. Should democracies stand idle as falsehoods erode public trust and poison civil discourse? Temporary censorship, when transparent and narrowly defined, can protect the very institutions that allow freedom to exist.

Yet, there's danger in giving the state this power. Who decides what is "harmful"? Who draws the line between dissent and danger? History is littered with examples of governments abusing censorship in the name of "security." The risk of overreach is real—and terrifying.

That’s why censorship in democracies must meet three ironclad criteria: necessity, transparency, and accountability. It should be a last resort, clearly explained, and always subject to independent oversight. Anything less opens the door to tyranny dressed in democratic clothing.

In the end, the question isn't whether censorship is ever justified—it's how, when, and by whom it’s done. A democracy that censors recklessly will not survive. But a democracy that fails to act in the face of chaos may also fall. The challenge is balancing liberty with responsibility, freedom with order.

Censorship in a democracy isn’t always the enemy—but it must never become the norm.

Censorship is often painted as a tool of dictators, used to silence dissent and suppress truth. Yet, even the most open democracies occasionally reach for this tool. Why? Because freedom isn't absolute—it exists within a framework of responsibility. The freedom to speak should not become the freedom to harm.

Take, for example, hate speech. When rhetoric incites violence or dehumanizes entire communities, can a democratic society truly afford to look away? If unchecked, such speech can fracture nations, fuel terrorism, or even lead to genocide. Here, censorship isn't oppression—it's prevention.

Or consider misinformation. In a digital age, lies can spread faster than facts, influencing elections, public health, and national security. Should democracies stand idle as falsehoods erode public trust and poison civil discourse? Temporary censorship, when transparent and narrowly defined, can protect the very institutions that allow freedom to exist.

Yet, there's danger in giving the state this power. Who decides what is "harmful"? Who draws the line between dissent and danger? History is littered with examples of governments abusing censorship in the name of "security." The risk of overreach is real—and terrifying.

That’s why censorship in democracies must meet three ironclad criteria: necessity, transparency, and accountability. It should be a last resort, clearly explained, and always subject to independent oversight. Anything less opens the door to tyranny dressed in democratic clothing.

In the end, the question isn't whether censorship is ever justified—it's how, when, and by whom it’s done. A democracy that censors recklessly will not survive. But a democracy that fails to act in the face of chaos may also fall. The challenge is balancing liberty with responsibility, freedom with order.

Censorship in a democracy isn’t always the enemy—but it must never become the norm.