The problem about culture is that it is multi-faceted and includes areas such as lifestyle, politics, behavior, history, mentality, faith and language. In order to succeed away from home, brands must cater to all of the above factors of each market they cater to. Companies which fail to accommodate and acknowledge these differences in culture either fail or have to face an arduous battle to replicate their success at home in other markets.

Apart from these international differences, one must also associate that a brand has its own culture. Just like companies misinterpret foreign audiences, they can also misinterpret foreign brands. So when a company like CBS went for inorganic growth by buying the guitar ompany Fender, it should have realized that it was not its market. The same can be said of Quaker Oats acquisition of the soft drink Snapple. In both cases, the parent company should have realized that their core competency did not lie in the acquired brand. Had they realized this, they would not have lost the millions they did eventually.

- A classic case would be the American baby food company Gerber. When they started selling baby food in Africa, they used the same packaging as in the USA i.e. the cute baby on the label. It was only later they found out that in Africa companies put pictures on the label of what is inside the container.

- Pepsodent did the exact opposite by marketing itself in South East Asia as something which whitens the teeth. What it did not know was that black teeth were considered attractive by the locals and they made elaborate efforts including chewing betel nuts to keep their teeth black.

- McDonalds spent thousands of dollars on trying to convince the Chinese consumer that they offer cheap food throughout the year through a TV ad. What they did not understand was that begging on national television does not equate to cheap; it is considered shameful.

- Nike, on the other hand, had packaging issues when it tried to sell golf balls in packs of four in Japan. The issue here was the number four. It sounds like death in Japanese.

- The film Hollywood Buddha ran into troubled waters in the island nations of Sri Lanka and Malaysia when its poster showed the lead actor sitting on the head of Lord Buddha. Something similar happened with Big Brother in the middle east when the local religious bodies protesting against showing men and women who are unmarried or not married to each other living together on air.

- When Microsoft showed some parts on Kashmir in a different light (read: shade of green) on a version of the Windows 95 OS, it had to recall 200000 copies of the offending software as the product was promptly banned in India. Needless to say, it cost them millions.

- The funniest example would be when at the African port of Stevadores, the time staff mistook the international symbol for fragile as broken. Multiple boxes of imported champagne were dumped into the sea as a result.

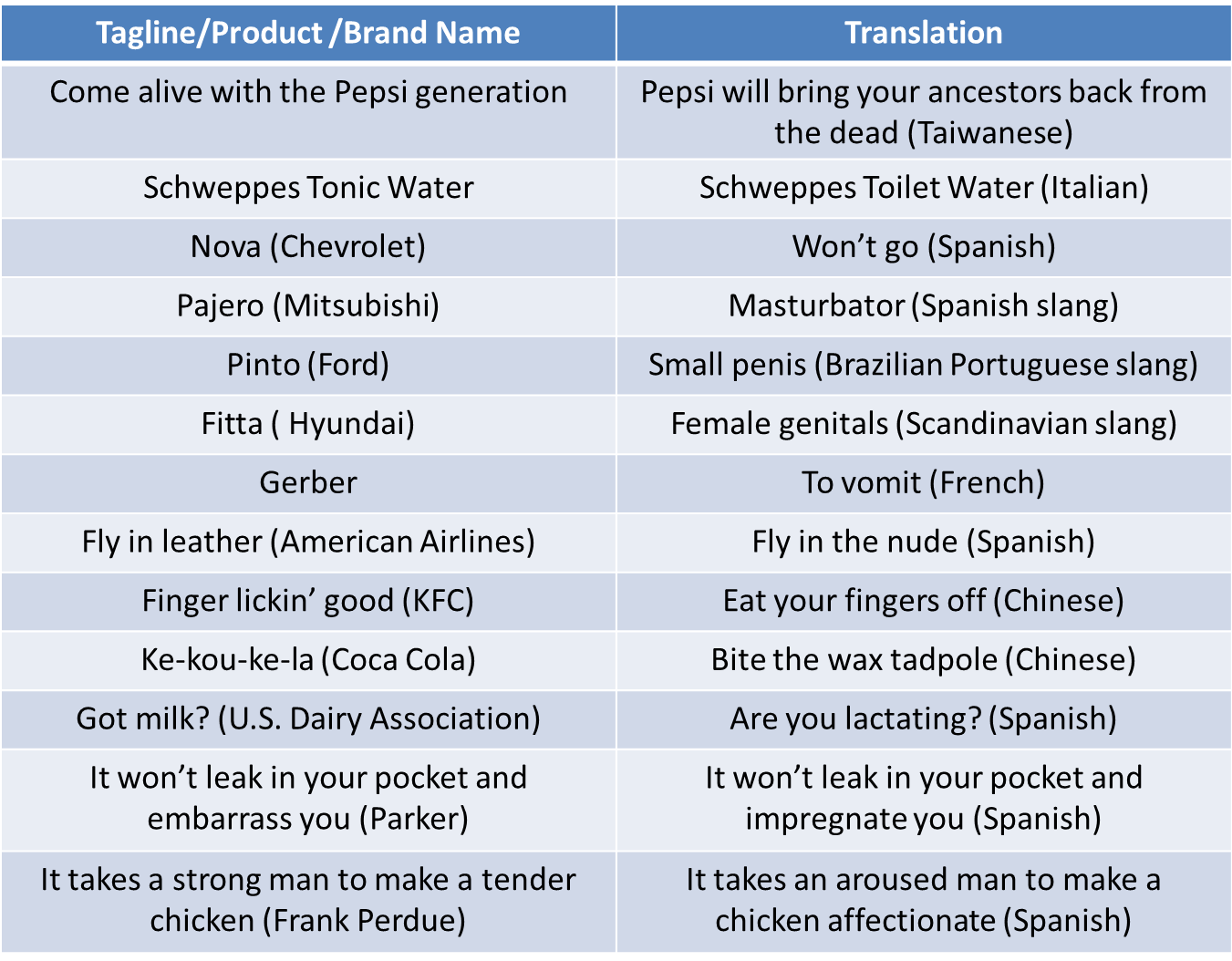

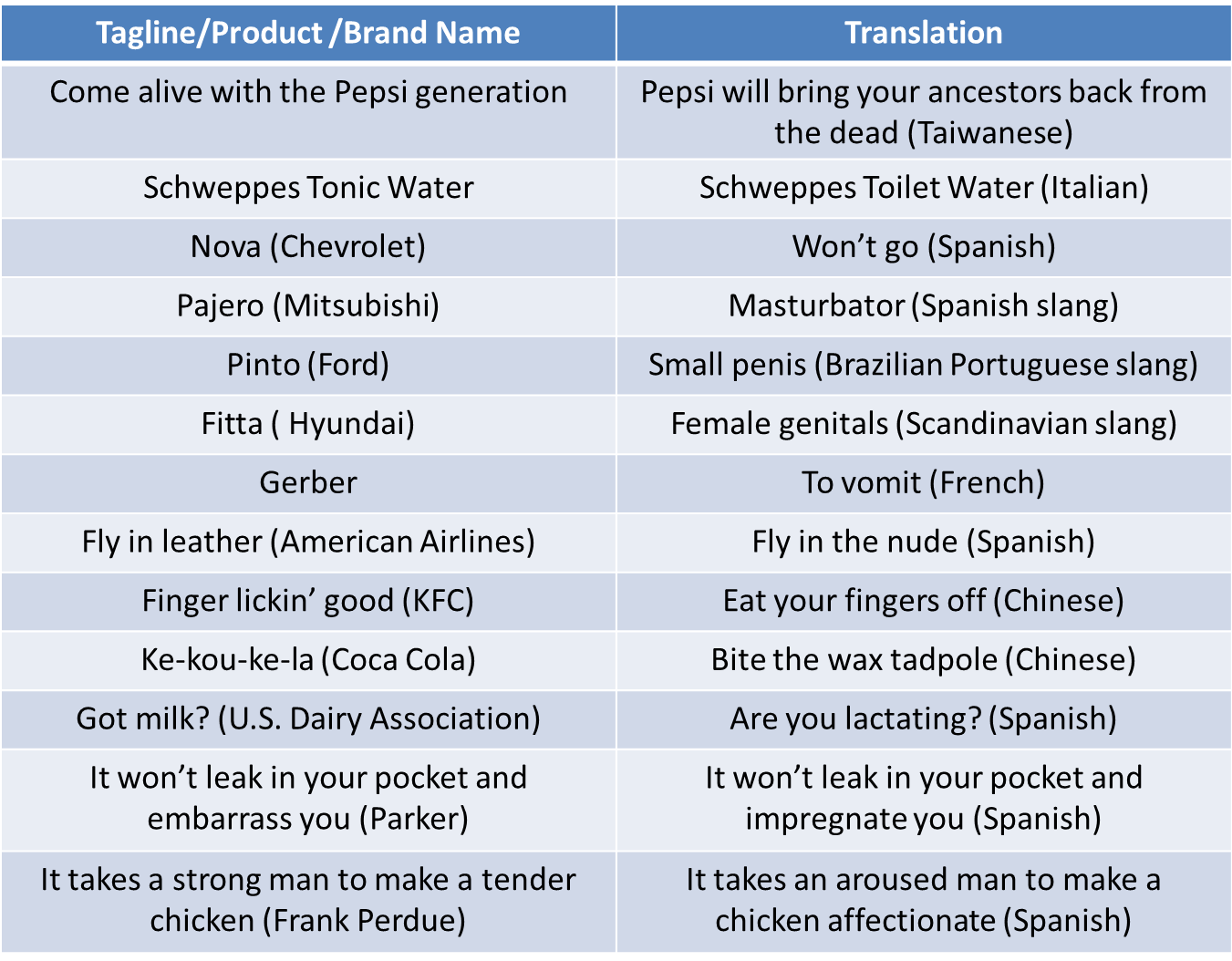

- Language has often been a major issue in cultural dissonance. Most companies do not want to tamper with their taglines. However their translations often leave more than a sour taste in the mouth. Some examples are given below

- Ikea had a workbench called Fartfull.

- Gerber (again!) in French means to vomit.

- Umbro had to remove its Zyklon range from the shelves as Zyklon was the gas used in the Nazi concentration camps.

- Honda had to rename the Fitta to Jazz as Fitta in the Scandinavian languages sound a lot like a vulgar representation of the female genitals.

Electrolux ran the Nothing sucks like an Electrolux campaign in the U.S. Your guess why it did not work would be as good as mine.

Mist in German means manure. So one can understand why the drink Irish mist did not do too well. Also Vicks does not do too well in Germany as V is pronounced like F in German.

Japanese FMCG products do not cross over too well simply because no one would like to buy Homo soap, Coolpis or Shito Mix.

Apart from these international differences, one must also associate that a brand has its own culture. Just like companies misinterpret foreign audiences, they can also misinterpret foreign brands. So when a company like CBS went for inorganic growth by buying the guitar ompany Fender, it should have realized that it was not its market. The same can be said of Quaker Oats acquisition of the soft drink Snapple. In both cases, the parent company should have realized that their core competency did not lie in the acquired brand. Had they realized this, they would not have lost the millions they did eventually.