For decades, computer graphics has been an arena of breathtaking innovation—from the pixelated sprites of early video games to the hyper-realistic CGI in blockbuster films. However, as the industry pushes relentlessly toward photorealism, a growing number of creatives and technologists are asking a bold question: Is the pursuit of visual perfection limiting artistic creativity?

Thanks to technologies like ray tracing, PBR (Physically-Based Rendering), GPU acceleration, and AI-driven upscaling, achieving near-lifelike visuals is now more attainable than ever. Games like Cyberpunk 2077 or movies like Avatar: The Way of Water showcase how far we've come. Even real-time engines like Unreal Engine 5 can render scenes with cinematic fidelity.

This has become the industry’s gold standard, especially in AAA gaming, VFX, and architectural visualization.

But here's the twist: while audiences marvel at lifelike imagery, an increasing number of developers and designers argue that the obsession with realism is suffocating stylistic expression.

One of the core criticisms is that photorealism demands enormous resources—both computational and human. Small studios or indie developers often can’t compete, forcing them to either conform or risk obscurity.

Furthermore, photorealistic design may limit the emotional impact of visuals. Think of games like Journey, Hades, or Cuphead—none of which chase realism, yet they are celebrated for their art direction and emotional storytelling.

As famed animator Hayao Miyazaki once said, “The world isn't just what we see. It's also what we imagine.”

Computer graphics is not just about simulation; it’s about communication. When stylization is dismissed in favor of mimicking reality, we risk homogenizing digital art. Everything starts to look the same—shiny, polished, and meticulously real—but emotionally hollow.

Is this what audiences want, or what we've trained them to expect?

This is particularly critical in fields like video games, where stylization often communicates narrative tone, cultural identity, and emotional cues more effectively than realism ever could.

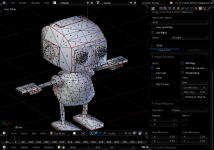

The pushback is already underway. Tools like Blender, Unity, and Procreate empower artists to prioritize style over realism. Stylized art is also more scalable and inclusive, enabling broader participation in the CG industry.

Meanwhile, platforms like ArtStation and Behance showcase a resurgence of abstract, painterly, and surreal styles gaining traction.

We need to ask: Should computer graphics always aim to mimic the physical world, or should it strive to express worlds we’ve never seen?

Computer graphics stands at a crossroads. Photorealism will always have its place, especially in simulations, education, and high-end media. But we must be careful not to let it become the sole definition of "quality" in digital art.

Let’s encourage diversity in visual language. Not everything needs to look like real life. In fact, the most memorable visuals often don’t.

The conversation around photorealism isn’t just technical—it’s philosophical. And that’s exactly why it matters.

The Rise of Photorealism

Thanks to technologies like ray tracing, PBR (Physically-Based Rendering), GPU acceleration, and AI-driven upscaling, achieving near-lifelike visuals is now more attainable than ever. Games like Cyberpunk 2077 or movies like Avatar: The Way of Water showcase how far we've come. Even real-time engines like Unreal Engine 5 can render scenes with cinematic fidelity.

This has become the industry’s gold standard, especially in AAA gaming, VFX, and architectural visualization.

But here's the twist: while audiences marvel at lifelike imagery, an increasing number of developers and designers argue that the obsession with realism is suffocating stylistic expression.

The Creative Cost of Realism

One of the core criticisms is that photorealism demands enormous resources—both computational and human. Small studios or indie developers often can’t compete, forcing them to either conform or risk obscurity.

Furthermore, photorealistic design may limit the emotional impact of visuals. Think of games like Journey, Hades, or Cuphead—none of which chase realism, yet they are celebrated for their art direction and emotional storytelling.

As famed animator Hayao Miyazaki once said, “The world isn't just what we see. It's also what we imagine.”

The Medium is the Message

Computer graphics is not just about simulation; it’s about communication. When stylization is dismissed in favor of mimicking reality, we risk homogenizing digital art. Everything starts to look the same—shiny, polished, and meticulously real—but emotionally hollow.

Is this what audiences want, or what we've trained them to expect?

This is particularly critical in fields like video games, where stylization often communicates narrative tone, cultural identity, and emotional cues more effectively than realism ever could.

Reclaiming Artistic Diversity

The pushback is already underway. Tools like Blender, Unity, and Procreate empower artists to prioritize style over realism. Stylized art is also more scalable and inclusive, enabling broader participation in the CG industry.

Meanwhile, platforms like ArtStation and Behance showcase a resurgence of abstract, painterly, and surreal styles gaining traction.

We need to ask: Should computer graphics always aim to mimic the physical world, or should it strive to express worlds we’ve never seen?

Final Thoughts: A Fork in the Pixelated Road

Computer graphics stands at a crossroads. Photorealism will always have its place, especially in simulations, education, and high-end media. But we must be careful not to let it become the sole definition of "quality" in digital art.

Let’s encourage diversity in visual language. Not everything needs to look like real life. In fact, the most memorable visuals often don’t.

The conversation around photorealism isn’t just technical—it’s philosophical. And that’s exactly why it matters.