'There's an India waiting to shine'

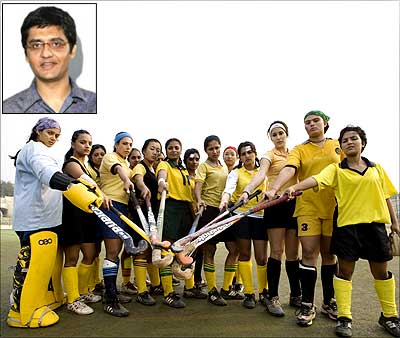

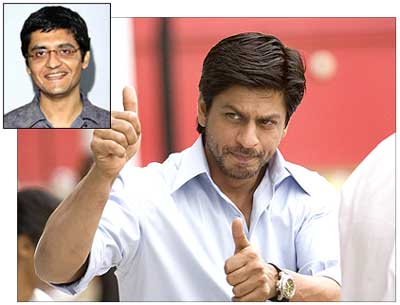

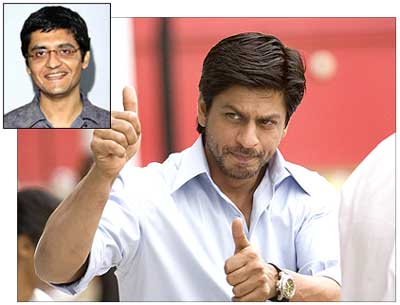

Chak De India, the movie that revived interest in our national sport, hockey. Inset: Jaideep Sahni

A few days ago, Jaideep Sahni got a call from a hockey equipment manufacturer telling him the sale of sticks has gone up 600%. Now, this isn't usually the kind of news that would be exultantly delivered to a scriptwriter, but then hockey hit Chak De India isn't your everyday film.

"I'm not stupid enough to believe that it's going to last," Jaideep shrugs, a uniquely modern Bollywood voice behind an infinitely mixed (Company, Jungle, Khosla Ka Ghosla, Bunty Aur Babli) bag of successes. Trapping him over a late evening cup of bitter espresso, we ask the writer about India and his vision for it.

He fits the bill perfectly. While contemporary writers breaking into the business continue to focus on edgy darkness, Jaideep�s tales are eventually optimistic, revolving around a simple morality. And there is a distinct India focus to it all, even in the gleefully evil Johnny Gaddaar title track.

Describing himself as "a pragmatist veering towards optimism," Jaideep finds an ideal beginning, unpredictably enough, via the insightful origins of Bunty Aur Babli.

Raja Sen met Jaideep to find out what he thinks of the emerging India.

'Why should their aspirations be different?'

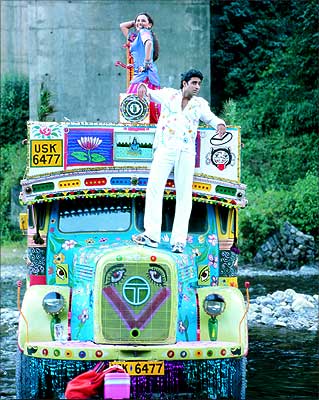

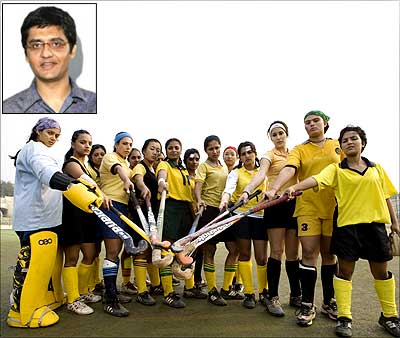

Bunty Aur Babli, a tale about youth from small towns and their determination to succeed.

Bunty... was a film about contrasting lifestyles between generations, of today's generation running out of patience. Aditya Chopra's germ of an idea thrilled Jaideep, and he set about it, randomly remembering media critic Shailaja Bajpai's book on the cable revolution in small town India -- something he'd read 10 years ago -- as well as equally old lessons learnt when he was in advertising.

Working on the 165-litre refrigerator brand for Kelvinator, Jaideep was made aware that his biggest competition, peculiarly enough, was the Bajaj scooter. "These were first time buyers, and the man of the house would have been dreaming of a second-hand scooter, and his wife dreamed of a fridge. There wasn't as much money around for both, and we realised that despite a completely different product category, yeh scooter ka hi chakkar hai." But as income increased, both fridge and scooter sales seemed the plateau. What was that first-time consumer suddenly spending his money on?

"We researched and found out that they're b***dy buying cable and colour TV. Matlab, I'm ready to go hungry or walk 12 miles to office, but I want my cable TV." This, coupled with Bajpai's book and the realisation that village kids in India were watching Baywatch on mute, was enough to convince the writer they were sharing dreams with us. "They are watching the same shows on the same channels, so why should their aspirations be any different from somebody in (southern Mumbai's posh) Cuffe Parade? Just that they haven't gotten the opportunities that we have, but they have the exposure to the same wants. They're as hungry, more hungry in fact."

'India C is not invited to the party'

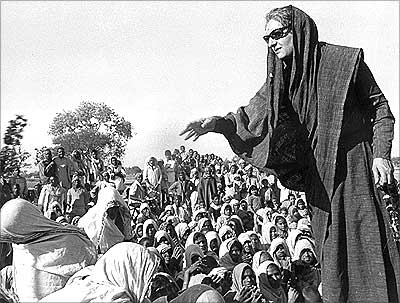

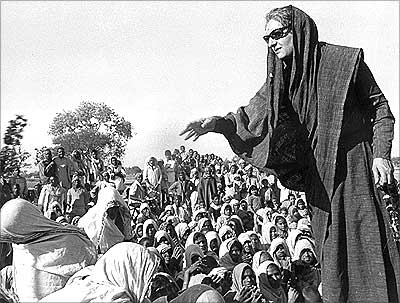

Then prime minister Indira Gandhi, a master of the grand public gesture.

In terms of India today, Jaideep is quick to make demarcations. "The way I see it there's an India A, India B and India C. India A is us, sitting here right now. We've come from pretty privileged backgrounds, as normal Indians go. We are the top 1% in terms of resources. We call ourselves upper middle-class, but are actually extremely high class as far as percentages go in India.

"India B is the India of Bunty Aur Babli, who sees us on cable and wants to be like that. Then there's India C, the tribals we used to watch dancing with Indira Gandhi when we were kids. You ask them who the prime minister is, they'll say Mahatma Gandhi. They are completely untouched by all this. So the market economy has touched India A, has touched India B, is on the rise in towns like Kanpur, etc. And India C is not invited to the party.

"They're the ones who are committing suicide," sighs the writer. "So this trickle-down, as they say, is happening. I'm aware it's happening. Whether it's happening fast enough, or in an equitable enough way, I don't think so. We don't make movies for them, we don't make any product for them. We don't even do government for them, some Naxalites are their government. There's a vacuum there, no?

"So they make their own movies. Bhojpuri movies are doing well, na? They have their own system of judiciary. The trickle-down is happening, opening up to the world is helping us and I'm all for it but there's an India which is shining, there's an India which is waiting to shine, and hungry for opportunities, which is Bunty Aur Babli, and there's an India which has no hopes in hell of ever shining, and we aren't even looking at them. That's not fair."

'I'm not for celebrating something without understanding'

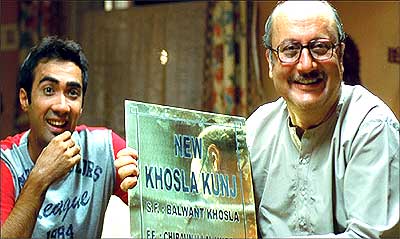

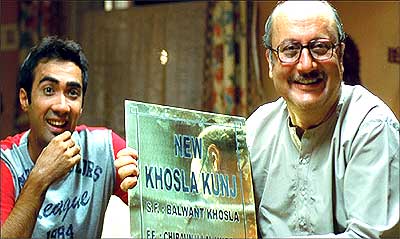

A scene from Khosla Ka Ghosla, a film about the battle against corruption.

He perceives India's problem as one of disparity, of a lack of balance. "The kind of films we are doing, it bothers me that they are shown only in multiplexes, that I'm not able to reach 70% of the country. It genuinely bothers me. Multiplexes help you track your revenue better, which is a good thing in a way because you can do a niche film, you can have success with a Khosla Ka Ghosla, but will the families who watched Khosla Ka Ghosla in multiplexes see it twice? I don't think so. It's good for me as a filmmaker, that I can make smaller, tighter films, make movies just for the art, which I like."

He illustrates the multiplex dilemma with a metaphor. "It doesn't make me happy when I travel on the Bombay-Pune Expressway and two-wheelers are not allowed. I don't like it when I'm racing down the Expressway and go from Bombay to Pune in two hours and the guy who can only afford a two-wheeler takes five hours. Why? What does it take to give them another lane? I asked them, 'Why don't you allow two-wheelers?' and they said 'No, they would slow down the traffic, it's a freeway.' So build them a separate lane, charge them 15 bucks or whatever. But let them get there in two hours, na? What is this rubbish? It's public land."

Jaideep is completely pro about free-enterprise, just believing the concept should be more accepting. "I'm not for government roads; I'm not for all that. But I'm also not for celebrating something without understanding. Which doesn't mean I understand perfectly; it just means I understand the need to have an understanding."

'We are basically decent people'

Rob Elliott/AFP/Getty Images

On the present generation's apathy towards all things rural, Jaideep is more hopeful than most. He considers us decent, unaware people too caught up in an economic boom to look at the rest of us. "We want to succeed and there are opportunities for us to succeed after a long time. We want to make the best of everything, and now. Which is great, I love it. Because we're in a hurry we don't have much time to look at India B or India C. But I'm confident that if our attention is drawn to it, we will. Because we are basically decent people."

"I think we can be more equitable," he says when asked to comment on the current Indian government, "which, in theory, the government seems to be preaching. I just don't know how much it is practising it. Perhaps it is. I love Dr Kalam's idea of urban infrastructure in rural areas. I love the work that micro-credit people are doing. I love the fact that the rural economy is growing in many areas."

"But I don't love the fact that most people are not aware of an experiment we had implemented, which I'd read in the Harvard Business Review 10 years back," he smiles at yet-another invaluable decade-old memory, digressing to grin and add the thought that's there's a movie in the story. "They went and put one telephone in a village in Karnataka. Just one telephone. Before the PCO boom started. They went after three years. The per-capita income of the village had gone up, multiple times. The middlemen were out of the vegetable market. The bank balances of an average villager had gone up many times. Some people from the village had gone abroad for the first time in their lives."

"Just access, and a telephone. What does it take? It takes us nothing to do it. The cable revolution and the telecom revolution have given this country the biggest fillip than what all of us imagine we have done. They are much bigger stories than all of us, and what any of us do."

'We need equality of opportunity'

A scene from Chak De India, a film about national pride and prejudice.

I just feel that the government's got its theory right, but we're in a time of coalition governments, and coalition governments, by their very nature, don't allow many theories to be converted to practice, because there are too many conflicting agendas. As a computer engineer myself, I'm willing to celebrate a Wipro. I love a Wipro, an Infosys. I love all of it," he says in a relentless rush, finally pausing to collect himself.

"But I believe that if you put the same operating system in Hindi and put it in a village, there will be an equality of opportunity and they'll be as good as anybody else."

SOURCE: http://specials.rediff.com/india60/2007/sep/20slide.htm

Chak De India, the movie that revived interest in our national sport, hockey. Inset: Jaideep Sahni

A few days ago, Jaideep Sahni got a call from a hockey equipment manufacturer telling him the sale of sticks has gone up 600%. Now, this isn't usually the kind of news that would be exultantly delivered to a scriptwriter, but then hockey hit Chak De India isn't your everyday film.

"I'm not stupid enough to believe that it's going to last," Jaideep shrugs, a uniquely modern Bollywood voice behind an infinitely mixed (Company, Jungle, Khosla Ka Ghosla, Bunty Aur Babli) bag of successes. Trapping him over a late evening cup of bitter espresso, we ask the writer about India and his vision for it.

He fits the bill perfectly. While contemporary writers breaking into the business continue to focus on edgy darkness, Jaideep�s tales are eventually optimistic, revolving around a simple morality. And there is a distinct India focus to it all, even in the gleefully evil Johnny Gaddaar title track.

Describing himself as "a pragmatist veering towards optimism," Jaideep finds an ideal beginning, unpredictably enough, via the insightful origins of Bunty Aur Babli.

Raja Sen met Jaideep to find out what he thinks of the emerging India.

'Why should their aspirations be different?'

Bunty Aur Babli, a tale about youth from small towns and their determination to succeed.

Bunty... was a film about contrasting lifestyles between generations, of today's generation running out of patience. Aditya Chopra's germ of an idea thrilled Jaideep, and he set about it, randomly remembering media critic Shailaja Bajpai's book on the cable revolution in small town India -- something he'd read 10 years ago -- as well as equally old lessons learnt when he was in advertising.

Working on the 165-litre refrigerator brand for Kelvinator, Jaideep was made aware that his biggest competition, peculiarly enough, was the Bajaj scooter. "These were first time buyers, and the man of the house would have been dreaming of a second-hand scooter, and his wife dreamed of a fridge. There wasn't as much money around for both, and we realised that despite a completely different product category, yeh scooter ka hi chakkar hai." But as income increased, both fridge and scooter sales seemed the plateau. What was that first-time consumer suddenly spending his money on?

"We researched and found out that they're b***dy buying cable and colour TV. Matlab, I'm ready to go hungry or walk 12 miles to office, but I want my cable TV." This, coupled with Bajpai's book and the realisation that village kids in India were watching Baywatch on mute, was enough to convince the writer they were sharing dreams with us. "They are watching the same shows on the same channels, so why should their aspirations be any different from somebody in (southern Mumbai's posh) Cuffe Parade? Just that they haven't gotten the opportunities that we have, but they have the exposure to the same wants. They're as hungry, more hungry in fact."

'India C is not invited to the party'

Then prime minister Indira Gandhi, a master of the grand public gesture.

In terms of India today, Jaideep is quick to make demarcations. "The way I see it there's an India A, India B and India C. India A is us, sitting here right now. We've come from pretty privileged backgrounds, as normal Indians go. We are the top 1% in terms of resources. We call ourselves upper middle-class, but are actually extremely high class as far as percentages go in India.

"India B is the India of Bunty Aur Babli, who sees us on cable and wants to be like that. Then there's India C, the tribals we used to watch dancing with Indira Gandhi when we were kids. You ask them who the prime minister is, they'll say Mahatma Gandhi. They are completely untouched by all this. So the market economy has touched India A, has touched India B, is on the rise in towns like Kanpur, etc. And India C is not invited to the party.

"They're the ones who are committing suicide," sighs the writer. "So this trickle-down, as they say, is happening. I'm aware it's happening. Whether it's happening fast enough, or in an equitable enough way, I don't think so. We don't make movies for them, we don't make any product for them. We don't even do government for them, some Naxalites are their government. There's a vacuum there, no?

"So they make their own movies. Bhojpuri movies are doing well, na? They have their own system of judiciary. The trickle-down is happening, opening up to the world is helping us and I'm all for it but there's an India which is shining, there's an India which is waiting to shine, and hungry for opportunities, which is Bunty Aur Babli, and there's an India which has no hopes in hell of ever shining, and we aren't even looking at them. That's not fair."

'I'm not for celebrating something without understanding'

A scene from Khosla Ka Ghosla, a film about the battle against corruption.

He perceives India's problem as one of disparity, of a lack of balance. "The kind of films we are doing, it bothers me that they are shown only in multiplexes, that I'm not able to reach 70% of the country. It genuinely bothers me. Multiplexes help you track your revenue better, which is a good thing in a way because you can do a niche film, you can have success with a Khosla Ka Ghosla, but will the families who watched Khosla Ka Ghosla in multiplexes see it twice? I don't think so. It's good for me as a filmmaker, that I can make smaller, tighter films, make movies just for the art, which I like."

He illustrates the multiplex dilemma with a metaphor. "It doesn't make me happy when I travel on the Bombay-Pune Expressway and two-wheelers are not allowed. I don't like it when I'm racing down the Expressway and go from Bombay to Pune in two hours and the guy who can only afford a two-wheeler takes five hours. Why? What does it take to give them another lane? I asked them, 'Why don't you allow two-wheelers?' and they said 'No, they would slow down the traffic, it's a freeway.' So build them a separate lane, charge them 15 bucks or whatever. But let them get there in two hours, na? What is this rubbish? It's public land."

Jaideep is completely pro about free-enterprise, just believing the concept should be more accepting. "I'm not for government roads; I'm not for all that. But I'm also not for celebrating something without understanding. Which doesn't mean I understand perfectly; it just means I understand the need to have an understanding."

'We are basically decent people'

Rob Elliott/AFP/Getty Images

On the present generation's apathy towards all things rural, Jaideep is more hopeful than most. He considers us decent, unaware people too caught up in an economic boom to look at the rest of us. "We want to succeed and there are opportunities for us to succeed after a long time. We want to make the best of everything, and now. Which is great, I love it. Because we're in a hurry we don't have much time to look at India B or India C. But I'm confident that if our attention is drawn to it, we will. Because we are basically decent people."

"I think we can be more equitable," he says when asked to comment on the current Indian government, "which, in theory, the government seems to be preaching. I just don't know how much it is practising it. Perhaps it is. I love Dr Kalam's idea of urban infrastructure in rural areas. I love the work that micro-credit people are doing. I love the fact that the rural economy is growing in many areas."

"But I don't love the fact that most people are not aware of an experiment we had implemented, which I'd read in the Harvard Business Review 10 years back," he smiles at yet-another invaluable decade-old memory, digressing to grin and add the thought that's there's a movie in the story. "They went and put one telephone in a village in Karnataka. Just one telephone. Before the PCO boom started. They went after three years. The per-capita income of the village had gone up, multiple times. The middlemen were out of the vegetable market. The bank balances of an average villager had gone up many times. Some people from the village had gone abroad for the first time in their lives."

"Just access, and a telephone. What does it take? It takes us nothing to do it. The cable revolution and the telecom revolution have given this country the biggest fillip than what all of us imagine we have done. They are much bigger stories than all of us, and what any of us do."

'We need equality of opportunity'

A scene from Chak De India, a film about national pride and prejudice.

I just feel that the government's got its theory right, but we're in a time of coalition governments, and coalition governments, by their very nature, don't allow many theories to be converted to practice, because there are too many conflicting agendas. As a computer engineer myself, I'm willing to celebrate a Wipro. I love a Wipro, an Infosys. I love all of it," he says in a relentless rush, finally pausing to collect himself.

"But I believe that if you put the same operating system in Hindi and put it in a village, there will be an equality of opportunity and they'll be as good as anybody else."

SOURCE: http://specials.rediff.com/india60/2007/sep/20slide.htm